Goldsmithing is not only an ancient art: it is a language that has traversed centuries, techniques and civilisations, shaping the most cherished symbols of our history and culture. From medieval crowns to the most avant-garde pieces of the 21st century, precious metalwork has been witness - and protagonist - of the social, aesthetic and spiritual transformations of Europe.

In this historical journey, we will take a closer look at the key moments in European goldsmithingThe medieval guilds, Renaissance splendour, Baroque sophistication, the industrial revolution and the emergence of signature jewellery.

With a special focus on Spain - and particularly Barcelona - we will explore how this art form has evolved without losing its essence.

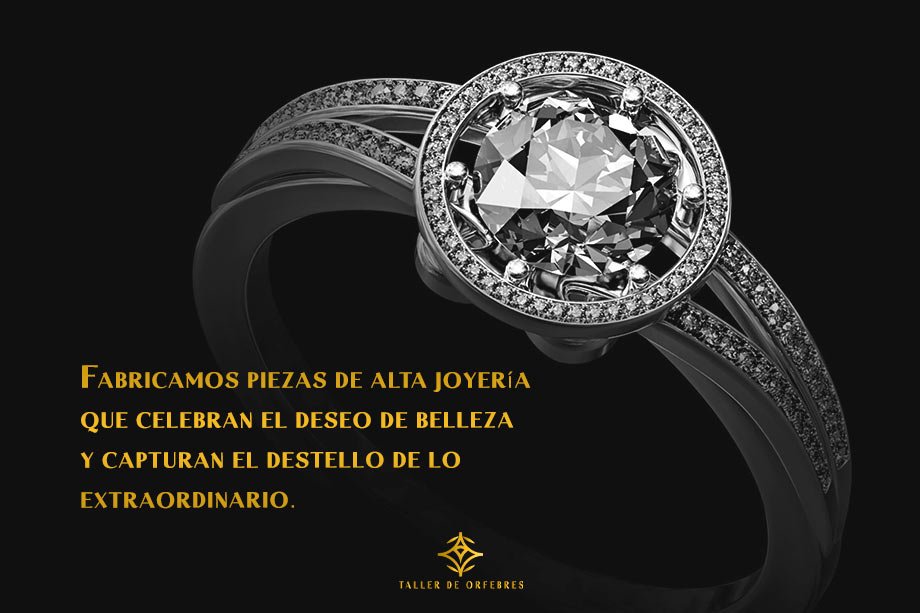

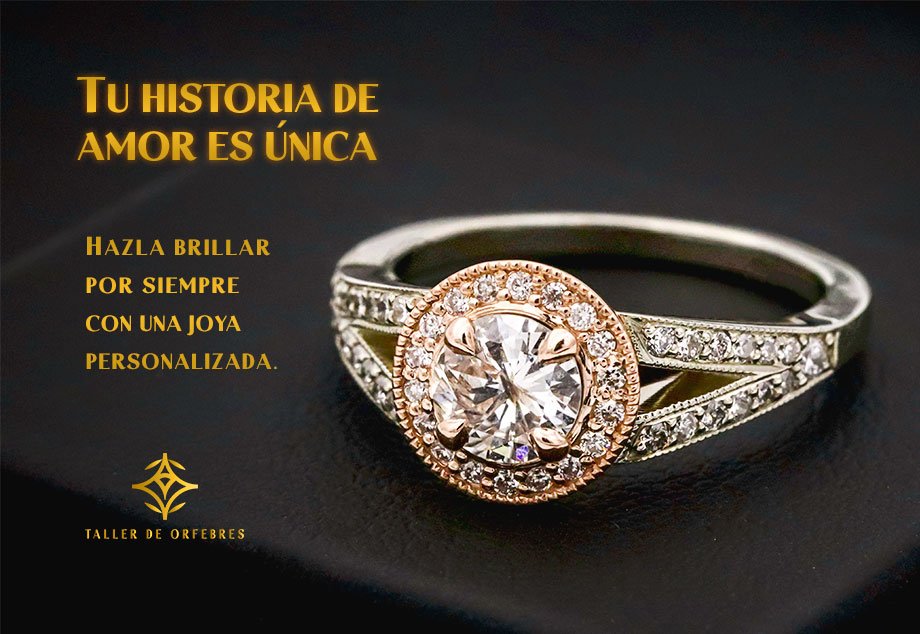

Today, Taller de Orfebres represents that unique confluence between tradition and avant-gardekeeping the legacy of craftsmanship alive through designer jewellery, personalised goldsmithing and processes that integrate centuries-old techniques with contemporary tools such as the 3D modelling.

In our workshops in Barcelona, each piece bears witness to this history: a bridge between the ancestral and the present, between the symbolic and the functional, between the inspiration of art and the precision of technique. We invite you to join us on this journey through the history of European goldsmithing, where beauty takes shape through fire, metal and the vision of the goldsmiths.

Medieval goldsmithing: between the sacred and the symbolic

During the Middle Ages, goldsmithing experienced a period of unprecedented splendour in Europe. In this context, the art of precious metals was not only an aesthetic expression: it was a tool of power and a vehicle of faith.

The medieval goldsmiths They worked in the service of churches, monarchies and nobles, creating pieces that symbolised the divine and the earthly: reliquaries, chalices, wreaths, processional crosses and seals that overflowed with symbolic and technical richness.

The goldsmiths' guilds gained enormous influence. These collectives jealously guarded their secrets, passing on their knowledge through rigorous training of apprentices. Thus was born a solid tradition of craftsmanship that still inspires workshops like ours, where mastery is cultivated piece by piece, generation after generation.

In the case of Spain, medieval goldsmithing stands out for the confluence of cultural influences. From the Visigothic imprint of the famous Treasure of Guarrazar (7th-8th centuries), with their exquisite votive wreaths, to the Islamic contributions of Al-Andalus -With new techniques in metallurgy and geometric decoration, Hispanic art developed a hybrid and refined style. The blending of Arabic and Christian motifs gave rise to a unique visual language that would distinguish Spanish goldsmithing in Europe.

In Catalonia, and especially in Barcelona, goldsmithing flourished at the same time as the Reconquest. The foundation of guilds of silversmiths turned the city into a hub of the trade. Today's Argentería Street still recalls the presence of those early silver workshops. Some of the most outstanding Catalan pieces include the silver throne of King Martin the Humane (late 14th century), preserved in the Cathedral of Barcelona, or the monumental processional cross of Gerona (15th century), both examples of the very high technical and symbolic level reached by the medieval Catalan goldsmiths.

Techniques such as cloisonné enamel or the watermark -The use of interwoven gold or silver threads was already being used to enhance liturgical objects and valuable jewellery. These craft practices are still alive and well today in projects of handmade jewellery who value detail, symbolism and craftsmanship.

It should be recalled that in the Middle Ages, goldsmithing was also a strategic business. The powerful employed trusted goldsmiths to create jewellery, heraldic rings or emblems to certify their authority. Thus, the goldsmith's art served at the same time the religious worship and secular powerThe work laid the foundations for a technical and symbolic tradition that is still alive and well in contemporary workshops.

Renaissance and Baroque: epochs of splendour

The Renaissance brought a new era of splendour to European goldsmithing. Inspired by classical art and the technical precision of the great Italian masters, workshops began to conceive pieces that fused sculpture, architecture and goldsmithing. One of the most influential references was Benvenuto Cellinithe Florentine goldsmith who set a school throughout Europe with his works in gold and silver with their sculptural and refined forms.

In Spain, the 16th century gave rise to the Plateresque style, which took its name from the elaborate work of the silversmiths (silversmiths). This style resulted in a profuse decoration, with classical motifs, mythological figures and symmetrical structures which sought balance and harmony. Liturgical works continued to be predominant, but now incorporated a new artistic language inherited from the renaissance humanism.

One of the greatest exponents of this stage is the Great Monstrance of the Cathedral of Toledoinitiated by Enrique de Arfe in 1515. Almost three metres high and made up of more than 5,000 assembled pieces, this masterpiece sums up the technical virtuosity of Spanish Renaissance goldsmiths. The Arfe family, like many others of the time, passed on their know-how from generation to generation, consolidating authentic goldsmith dynasties.

Towards the end of the 17th century, artistic influence began to shift towards France. The style Louis XV and the Late Baroque They brought with them a more exuberant aesthetic: asymmetrical curves, flowers, garlands, raised angels and richly ornamented surfaces. This decorative trend invaded not only churches, but also palaces and mansions throughout Europe.

In Spain, and especially in Catalonia, this period was equally fertile. Between 1670 and 1730, the large-format ecclesiastical commissionsas rococo urns-reliquary, monumental candlesticks y custodians in chiselled silver. Master silversmiths such as the Tramullas, Pere Llopart o Joan Matons works of great visual and symbolic impact were carried out, such as the Sant Ermengol urn (La Seu d'Urgell) or the urn of Santa Cinta (Tortosa), considered the summits of the rococo Catalan goldsmith.

However, this heyday began to decline in the late 18th century. The wars of succession and Napoleonic invasions paralysed sumptuary commissions and affected the craft economy. At the same time, the guild system went into crisis: the number of master goldsmiths decreased drastically, especially in cities such as Barcelona, where the silversmiths' guild fell between 1800 and 1814.

This opened the way for the transformation of the profession: the traditional goldsmithing was ushering in a new era marked by the industrialisationbut not without beauty and know-how.

Renaissance vs. Baroque in goldsmithing

| Feature | Renaissance Goldsmithing | Baroque and Rococo Goldsmithing |

| Epoch | 16th century (1500-1600) | 17th-18th centuries (1600-1780) |

| Inspiration | Classical art, balance, symmetry | Movement, theatricality and decorative exuberance |

| Main techniques | Fine chiselling, filigree, assembling | Ornate reliefs, ornamental sculpture |

| Motives | Mythological figures, columns, scrolls | Wreaths, angels, curves, flowers |

| Iconic examples | Great Custody of Toledo | Urn of Sant Ermengol, Baroque Custodies |

| Functional approach | Religious devotion + technical virtuosity | Liturgical and decorative display |

| Regions highlighted | Italy, Castile, Aragon | France, Catalonia, Andalusia |

At Taller de Orfebresthis renaissance and baroque legacy lives on. Many of the historical techniques, such as hand chiselling, enamelling or the modular construction of pieces, are part of our current creative process, now enhanced by contemporary tools.

19th century: the challenge of industry and the resilience of the jewellery trade

The 19th century was a turning point for European goldsmithing. The advent of the Industrial Revolution radically transformed production methods, also in the field of jewellery. Techniques such as electroplating (electrochemical gold or silver plating) or the use of mechanical dies allowed parts to be mass-produced, reducing costs and democratising access to metal decorations.

This industrialisation, however, came at a cost: it partially displaced craft production and accelerated the decline of the guild system. In Barcelona, for example, the compulsory guild apprenticeship for goldsmiths was abolished in 1852, a clear sign of the end of an era.

But far from disappearing, the handmade goldsmithing was able to adapt. Many jewellery families They kept tradition alive, modernising without renouncing technical excellence or the symbolic value of each piece. Barcelona witnessed this evolution: historic workshops - first located on Argentería street and then on the elegant Passeig de Gràcia - offered signature jewellery to a rising Catalan bourgeoisie eager to express their status through discreet, well-crafted luxury.

Surnames such as Masriera, Careers, Bagués o Cabot shone during this period, positioning the city as a reference point for fine handcrafted jewellery. His creations still inspire brands such as Taller de Orfebreswhich takes up this legacy with a contemporary vision.

In terms of styles, the 19th century was marked by a strong historicist nostalgia. Medieval and Renaissance forms were revalued, with jewellery such as cameos, Gothic crosses, calligraphic brooches and romantic miniatures. This emotional aesthetic connected with a public that sought beauty with symbolic depth.

At the end of the century, the winds of change brought in new currents: the Art Nouveaucalled in Catalonia ModernismeThe Spanish goldsmith's art, with its organic forms and its fusion of art and nature, was beginning to make its mark. But before this revolution, Spain still kept alive many regional traditions of goldsmithing:

- At Cordobathe silver filigree decorated traditional combs and jewellery.

- At Toledothe ancient art of damasceneinlaying gold into black steel with precision and beauty.

- At Galiciathe jewels of silver and jetwith strong popular roots.

This regional richness contributed unique nuances to the identity of the spanish handmade jewelleryeven in the middle of the industrial age.

Catalan Modernism

As we mentioned, at the end of the 19th century, Catalonia was the birthplace of an artistic revolution that also transformed jewellery: the Modernisme. This style, heir to the Art Nouveau European, it was characterised by its organic, asymmetrical and fluid forms, inspired by nature.

Dragonflies, leaves, flowers and curved lines populated brooches, pendants and rings, elaborated with exquisite techniques such as the translucent enamelthe fine chiselling or the use of baroque pearls. Figures such as Masriera i Rosés positioned Catalan jewellery at the forefront of European jewellery.

Today, this legacy continues to inspire designs that combine formal freedom, sensuality and master craftsmanship.

In short, the nineteenth century was a century of creative tension between tradition and innovation. Centuries-old techniques - such as hand chiselling, fire enamelling and hand-setting stones - coexisted with mechanical processes that multiplied production. Barcelona and Spain knew how to navigate this change, laying the foundations for the creative explosion of the Modernism that would forever transform the history of art and jewellery.

Modernism and early 20th century avant-garde: jewellery as a total art form

With the beginning of the 20th century, the Catalan goldsmiths underwent a real transformation. The period of the Modernisme (ca. 1890-1910) was a milestone in his conception of the jewellery not only as an ornamentbut as symbolic work of art. Inspired by the European Art Nouveaumodernist jewellers fused nature, technique and poetry in pieces that overflowed with imagination and mastery.

One of the big names of this period was Lluís Masriera i RosésBarcelona-born goldsmith who revolutionised the aesthetics of jewellery. Masriera introduced into his creations organic forms -dragonflies, nymphs, flowers- and exquisite techniques such as plique-à-jour enamelShe was the first woman to create her own designs, achieving transparencies and vibrant colours. Her pendants, brooches and tiaras - with gold, precious stones and pearls - conquered even royalty: in 1906 she designed a bridal tiara for Queen Victoria Eugeniea gift from the Catalan bourgeoisie, now disappeared but remembered as a symbol of an era of splendour.

After Modernism, new languages emerged. The Noucentisme (1910-1920) recovered the classical sobriety and pure forms, anticipating the Art Deco of the 1920s: geometric lines, elegant symmetry and more restrained luxury. This was the context in which the catalan high jewellery The jewellery shops moved from the Gothic Quarter to the Passeig de GràciaThe art deco shop windows became temples of design.

Collaboration between goldsmiths and avant-garde artists reached its peak. Supported by institutions such as the Foment de les Arts Decoratives (FAD)jewellers worked side by side with sculptors and painters. Ismael Smith designed dreamlike jewellery; later on, figures such as Pablo Gargallo o Julio González brought their sculptural vision to pieces that crossed the boundaries between jewellery, sculpture and art object.

In 1925, a number of Catalan jewellers exhibited at the Paris International Exhibitionand in 1929, the Barcelona Exhibition included a prominent section on artistic jewelleryThe city has become an international benchmark. Among the most innovative proposals were Manuel Capdevilaa young goldsmith who, in 1937 in Paris, presented a series of abstract and modern brooches. Although they went unnoticed at the time, today they are valued as pioneering examples of contemporary designer jewellery.

Unfortunately, the brilliant path of the Spanish goldsmiths was cut short by the Civil War (1936-1939). The post-war period and Franco's dictatorship brought shortages, repression and the closure of workshops. The goldsmiths survived as best they couldoften melting down old pieces to reuse the metal, while creativity was put on hold. Some liturgical treasures were salvaged and preserved in museums, and a few family sagas -The custodians of know-how have managed to keep the flame of the craft alive.

Today, in Taller de Orfebresthat legacy lives on. We honour the modernist, art deco and avant-garde heritage not as a frozen past, but as an inexhaustible source of inspiration to create jewellery with soul in the present.

Second half of the 20th century: revival of tradition and new creative languages

After the dark years of the post-war period, the Spanish goldsmiths began to recover vitality from the 1960s onwards. With the economic and cultural opening up of the end of Franco's regime, interest in the jewellery as a form of artistic expression.

A key role in this revival was played by Manuel CapdevilaHe was the heir to a dynasty of Catalan goldsmiths, who continued to explore the abstract and sculptural potential of jewellery. His creations, influenced by the European avant-garde movements, consolidated an experimental language that placed the Catalan goldsmiths in tune with what was happening in Italy, Germany and France. Alongside them, designers such as Anna Font contributed to recovering the symbolic, material and artistic value of contemporary jewellery.

During the 1970s and 1980s, with the advent of democracy, the Barcelona's jewellery scene was experiencing a period of great plurality. While the traditional houses were modernising their collections for a new generation of clients, the signature jewellerywhere designer-craftsmen produced unique pieces, charged with aesthetic and conceptual intention.

Barcelona became a veritable creative incubator. Schools such as the Escola Massana (founded in 1929), the Escola Llotjaand later the speciality of Artistic Jewellery in the School of Applied Arts (1969), trained a new generation of artist-jewellers. Modern guild institutions were also consolidated, such as the JORGC (Official Association of Jewellers, Goldsmiths, Watchmakers and Gemmologists of Catalonia), which promoted the professionalisation of the sector.

Contact with international trends, such as the Pop Artthe minimalism or the postmodernismexpanded creative horizons. Many designers began to incorporate non-traditional materials -steel, titanium, resins, glass- together with noble metals, expanding the aesthetic language of jewellery.

The contemporary jewellery began a dialogue with the fashion, sculpture and conceptual art. It was exhibited at international fairs, galleries and museums, leaving behind its merely decorative role. A key milestone was the creation, in the 1990s, of a public collection of more than 200 pieces in the Valencian Institute of Modern Art (IVAM)which legitimised signature jewellery as an art form in its own right.

At the close of the 20th century, Spain already had a solid core of contemporary creators.The goldsmith sector is increasingly connected to the world of design and culture.

Today, in Taller de OrfebresWe feel we are an active part of this continuity: we combine ancestral techniques with a contemporary outlook to continue creating jewellery that not only adorns, but also expresses, evokes and remains.

Find out how we transform your ideas into unique pieces of handmade jewellery.

21st century: traditional craftsmanship and cutting-edge technologies in goldsmithing

In the 21st century, the handmade goldsmithing has not only survived: it has been reborn with a vengeance. In the face of the uniformity of industrial production, the value of manual work, the uniqueness of each piece and the legacy of ancient crafts have taken on a new relevance. Today, the goldsmith's art is seen as a living heritagewhich dialogues with innovation without renouncing its soul.

This is precisely the focus of Taller de Orfebreswhere traditional techniques - such ashand-chiselled, filigree, engraving, hand-setting, hand-engraving- coexist with digital tools such as the CAD design and 3D printing. This combination makes it possible to create contemporary jewellery of extreme precision, without losing the emotional and symbolic character of the handmade pieces.

Barcelona has established itself in recent years as a capital of artistic jewellery in Spain where fairs such as BCNjoya The diversity of today's jewellery ecosystem is evident: from conceptual jewel-sculptures to refined pieces of fine handcrafted jewellery.

As far as materials are concerned, the 21st century has expanded the goldsmith's palette as never before. titanium, palladium, damascened steel, resins, exotic woods, ceramics, recycled materials and even biocompatible materials.. The sustainability has become a differential value: more and more workshops are opting for the recycled metals, traceable or ethically sourced gemstonesand environmentally friendly processes.

But despite the technological revolution, the basics of the craft remain intact. In a workshop in Barcelona, the apprenticeship still starts with the hand-held saw, blowtorch, hand polishing or fire enamelling. The difference is that today, the same apprentice also masters the 3D digital modellingthe microfusionthe laser welding and the augmented reality for prototyping.

The result is a new generation of hybrid jewellersable to honour the medieval heritage and embrace the future with creativity, precision and awareness.

To conclude, we share this summary table that synthesises this extensive journey through the eras, styles and technical developments that have marked the art of jewellery throughout history:

| Historical period | Characteristics of goldsmithing | Some of the most important examples are |

| Middle Ages (5th-15th c.) | Craft guilds; production centred on religious objects (crosses, chalices, reliquaries); cloisonné enamel, filigree and engraving techniques; strong Christian symbolism. | Treasure of Guarrazar; Processional cross gilded with enamels, Gerona Cathedral. |

| Renaissance (16th c.) | Italian influence (classicism and technical virtuosity); Spanish Plateresque style; incorporation of mythological and profane iconography. | Greater monstrance of Toledo, Enrique de Arfe; Court jewellery with cameos and carved gems. |

| Baroque (17th-18th c.) | Predominance of French Louis XV style; splendour of Baroque and Rococo sacred goldsmithery; boom in large-scale silver carvings. | Reliquary urn of Sant Ermengol; Crown and sceptre of the Catholic Monarchs; Processional monstrance of Seville. |

| 19th century | Decline of the guild system; mechanisation of production; historicist and romantic styles; democratisation of jewellery. | Elizabethan jewellery; filigree combs; family workshops such as Masriera. |

| Modernism (end of 19th century - beginning of 20th century) | Art Nouveau aesthetics: organic designs inspired by nature; techniques such as plique-à-jour enamelling; jewellery as a work of art. | Saint George and the dragon pendant by Masriera; Brooches with opaline and enamel. |

| Art Deco and Avant-Garde (1920s-1930s) | Geometric and stylised designs; collaboration of jewellers with avant-garde artists; first exhibitions of jewellery as an artistic expression. | Art Deco platinum and diamond brooches; Abstract brooches by Capdevila; Surrealist jewellery by Dalí. |

| Post-war and late 20th century (1940-1980) | Post-war shortages; resurgence of artistic jewellery in the 1960s; incorporation of new materials; founding of specialised schools. | Works by Manuel Capdevila; Experimental jewellery with Pop Art and minimalist influences; Massana School. |

| 21st century (2000-present) | Fusion of tradition and technology; use of CAD, 3D printing and recycled metals; rise of signature jewellery; international events such as JOYA Barcelona. | JOYA Barcelona Fair; Pieces with traditional filigree and CAD design; Use of anodised titanium and sustainable materials. |

Taller de Orfebres: where tradition meets the avant-garde

Throughout this historical journey, we have seen how the European goldsmiths has been able to reinvent itself century after century, remaining true to its artisanal essence while adapting to new styles, materials and technologies.

Nowhere is this continuity more clearly seen than in BarcelonaThe city was the cradle of medieval guilds, the epicentre of the Modernisme jewellery and today an international benchmark for contemporary jewellery.

At Taller de Orfebres we carry that heritage in our hands. Every piece we create is born out of a deep respect for the traditional techniques -It is projected into the future through digital tools such as 3D design, prototype printing and new experimental finishes.

Our philosophy is clear: to unite the best of two worlds. On the one hand, the patience of the craftsmanthe precision of manual workthe beauty of the imperfect. On the other, the conscious innovationThe language of contemporary design and the possibility of exploring new forms of expression.

Each piece of jewellery born in our workshop is unique. It carries in itself centuries of historybut also the pulse of the present. We honour the past to make it shine in the present. And so, piece by piece, we contribute to the art of goldsmithing remaining what it has always been: a craft that transforms matter into symbols, and technique into a testimony of an epoch..

Bibliography and sources:

The historical information in this article is based on a variety of sources specialising in the history of jewellery and goldsmithing, including academic texts, journalistic publications and museum contents.

Notable references include Wikipedia (articles: History of goldsmithing, Treasure of Guarrazar, etc.) and museum catalogues (Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya, Museo Arqueológico Nacional).

We hope that this tour has been enjoyable and illustrative, reinforcing the appreciation of the artistic, cultural and technical value of goldsmithing from the Middle Ages to the present day.

Main sources consulted:

- Gómez-Moreno, M. (1952). The sumptuary arts in Spain. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe.

- Bassegoda, J. (2001). Lluís Masriera i Rosés: the modernist jeweller. Barcelona: Publicacions de l'Abadia de Montserrat.

- Ferrer, M. (1993). Jewellery in Spain: history and evolution. Madrid: Fundación Caja de Madrid.

- Prado Museum - Decorative arts collection

- JORGC - Col-legi Oficial de Joiers, Orfebres, Rellotgers i Gemmòlegs de Catalunya (Official College of Jewellers, Goldsmiths, Rellotgers and Gemmologists of Catalonia)